|

“ENRIQUE MARTIN” (from LAST EVENINGS ON EARTH)

ROBERTO BOLAÑO

for Enrique Vila-Matas

A poet can endure anything. Which amounts to saying that a human being can endure anything. But that’s not true: there are obviously limits to what a human being can endure. Really endure. A poet, on the other hand, can endure anything. We grew up with this conviction. The opening assertion is true, but that way lie ruin, madness, and death.

I met Enrique Martin a few months after arriving in Barcelona. He was born in 1953 like me and he was a poet. He wrote in Castilian and Catalan with results that were fundamentally similar, though formally different. His Castilian poetry was well meaning, affected, and quite often clumsy, without the slightest glimmer of originality. His model (in Castilian) was Miguel Hernández, a good poet whom, for some reason, bad poets seem to adore (my explanation, though it’s probably simplistic, is that Hernández writes about pain, impelled by pain, and bad poets generally suffer like laboratory animals, especially during their protracted youth). Enrique’s Catalan poetry, by contrast, was about real things and daily life, and only his friends ever read or heard it (although, to be perfectly frank, the same is probably true of what he wrote in Castilian; the only difference, in terms of audience, was that he published the Castilian poems in magazines with tiny circulations, seen only, I suspect, by his friends, if at all, while he read the Catalan poems to us in bars or when he came around to visit). Enrique’s Catalan, however, was bad (how he managed to write better poems in a language he hadn’t mastered than in his mother tongue must, I suppose, be numbered among the mysteries of youth). In any case Enrique had a very shaky grasp of the rudiments of Catalan grammar and it has to be said that he wrote badly, whether in Castilian or in Catalan, but I still remember some of his poems with a certain emotion, colored no doubt by nostalgia for my own youth. Enrique wanted to be a poet, and he threw himself into this endeavor with all his energy and willpower. He was tenacious in a blind, uncritical way, like the bad guys in westerns, falling like flies but persevering, determined to take the hero’s bullets, and in the end there was something likable about this tenacity; it gave him an aura, a kind of literary sanctity that only young poets and old whores can appreciate.

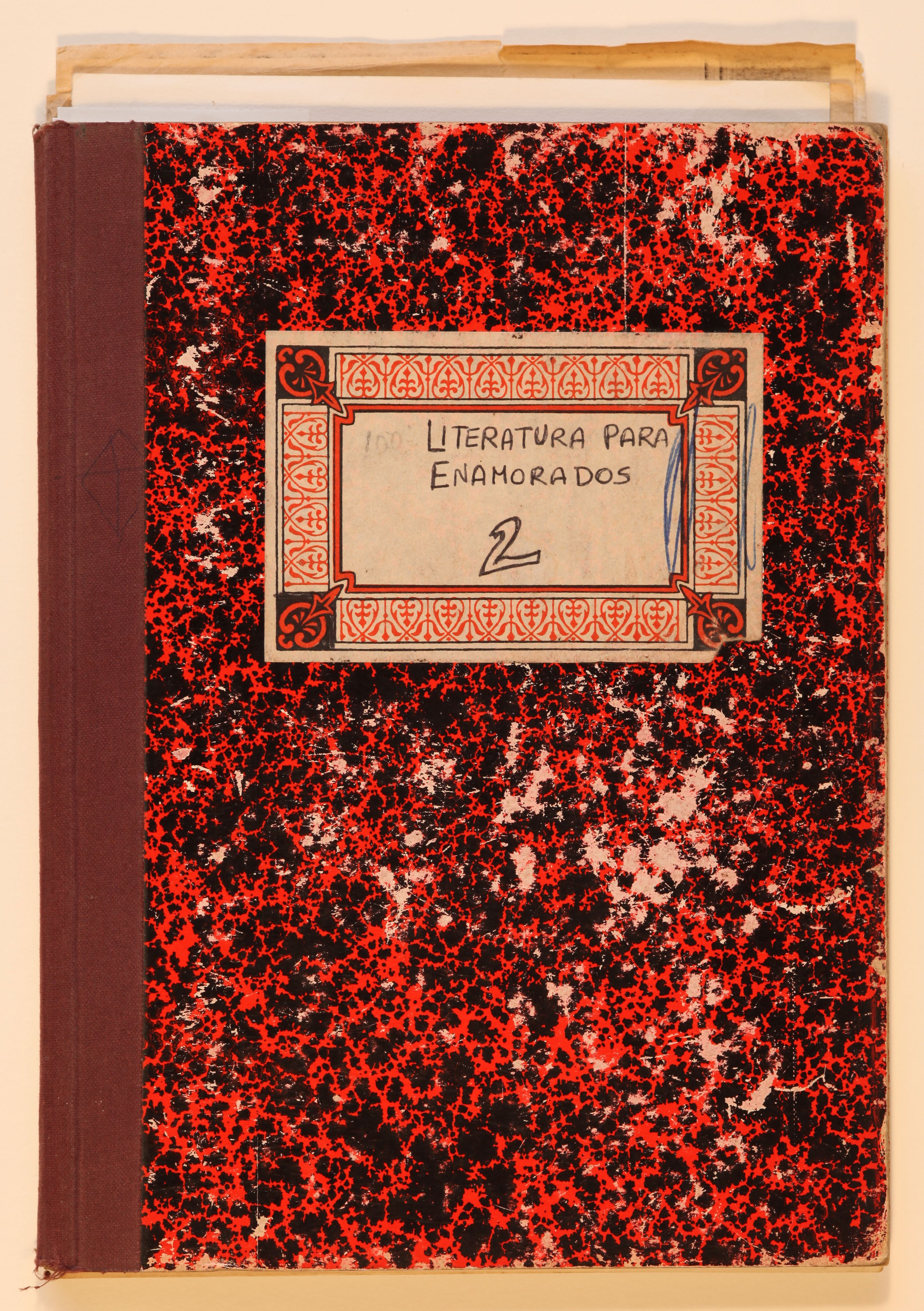

At the time I was twenty-five and thought I had done it all. Enrique was the opposite: there were so many things he wanted to do, and, in his own way, he was preparing to take on the world. His first step was to bring out a literary magazine, or fanzine, really, which he financed with his savings (he had been working in some obscure office near the port since he was fifteen). At the last minute, Enrique’s friends (and one of mine among them) decided not to include my poems in the first issue, an incident that, I am ashamed to admit, led to an interruption of our friendship. According to Enrique, it was the fault of another Chilean, an old friend of his, who had opined that two Chileans was one Chilean too many for the first issue of a little magazine devoted to Spanish writing. I was in Portugal at the time, and when I got back, I decided that was it: I would have nothing more to do with the magazine and it would have nothing more to do with me. I refused to listen to Enrique’s explanations, partly because I couldn’t be bothered, partly to assuage my wounded pride, and I washed my hands of the whole business.

We didn’t see each other for a while. But in the bars of the Gothic Quarter I would sometimes run into mutual acquaintances, and they kept me laconically informed of Enrique’s latest adventures. That’s how I found out that the magazine (prophetically named White Rope, although I’m sure it wasn’t his idea) had folded after the first issue, and that the first performance of a play he had tried to put on at a cultural center in the Nou Barris district had been greeted with boos and jeers, and that he was planning to launch another magazine.

One night he turned up at my apartment. He was carrying a folder full of poems and he wanted me to read them. We went out to dinner at a restaurant in the Calle Costa and over coffee he read me a few of the poems. He awaited my judgment with a mixture of a self-satisfaction and fear. I realized that if I said they were bad, I would never see him again, as well as getting myself into an argument that could easily continue into the small hours. I said I thought they were well written. I wasn’t overly enthusiastic, but carefully avoided the slightest criticism. I even said I thought one of them was very good, in the manner of León Felipe, a nostalgic poem about the landscapes of Extremadura, where Enrique had never lived. I don’t know if he believed me. He knew I was reading Sanguinetti at the time and subscribed (though not exclusively) to the Italians views on modern poetry, so I could hardly be expected to admire his verses about Extremadura. But he pretended to believe me; he pretended to be glad he had read me the poems and then, revealingly, he started talking about the magazine that had perished after the first issue, and that’s when I realized that he didn’t believe me but wasn’t going to say so.

That was it. We talked a while longer, about Sanguinetti and Frank O’Hara (I still like Frank O’Hara but I haven’t read Sanguinetti for ages), about the new magazine he was planning to launch (he didn’t invite me to contribute), and then we said good-bye in the street, near my house. It must have been a year or two before I saw him again.

At the time I was living with a Mexican woman and it looked as if the relationship would be the death of her, and me, and the neighbors, and sometimes even the people who ventured to pay us a visit. Once was enough for our unfortunate visitors, and soon we were hardly seeing anyone. We were poor (although the woman came from a well-to-do family in Mexico City, she absolutely refused all their offers of financial assistance); our battles were Homeric and a dark cloud seemed to be looming over us day and night.

That’s how things were when Enrique Martin reappeared. As he crossed the threshold with a bottle of wine and some French pâté, I had the impression he had come as a spectator, to watch the final act of a major crisis in my life (although, in fact, I felt fine, it was my girlfriend who was feeling rotten), but later, when he invited us to dinner at his place, and was so keen to introduce us to his girlfriend, I realized that he hadn’t come to observe but, probably, to be observed, or possibly even because, in a sense, my opinion still mattered to him. I know I didn’t appreciate this at the rime. For a start, I was annoyed by his sudden appearance, and tried to make my greeting sound ironic or cynical, though it probably just sounded apathetic. To be honest, in those days, I wasn’t fit company for anyone. This was common knowledge: people avoided me or fled my presence.

But Enrique wanted to see me, and for some mysterious reason, the Mexican woman liked Enrique and his girlfriend, so we ended up having a series of meals together, five in all.

Naturally, by the time we resumed our friendship— though the term is no doubt excessive—we disagreed about almost everything. My first surprise came when I saw his apartment (when our ways had parted he was still living with his parents and although I later heard that he was sharing a place with three friends, for one reason or another I never went there). Now he had a loft in the Barrio de Gràcia, full of books, records, and paintings, a large though perhaps rather dim dwelling that his girlfriend had decorated with eclectic taste, and they had some interesting things: objects picked up on recent trips to Bulgaria, Turkey, Israel, and Egypt, some of which were more than tourist souvenirs or imitations. My second surprise came when he told me that he had stopped writing poetry. He said this after dinner, in the presence of my girlfriend and his, although the confession was in fact directed specifically at me (I was playing with an enormous Arab dagger, with ornamental work on both sides of the blade; it can’t have been very practical to use), and when I looked up he was smiling as if to say, I’ve grown up, I’ve realized you can enjoy art without making a fool of yourself, without keeping up some pathetic pretense of being a writer.

The Mexican woman (who was forthright to a fault) thought it was a shame he had given up; she made him tell the story of the magazine in which my poems hadn’t appeared, and in the end she judged the arguments that Enrique had marshalled in defense of his renunciation to be sound and sensible, but predicted that before too long he would be writing again with renewed vigor. Enrique’s girlfriend agreed with her completely, or almost. Both women seemed to think (although Enrique’s girlfriend, for obvious reasons, held this opinion more strongly than mine) that his decision to concentrate on his job—he’d been promoted, which meant he had to travel to Cartagena and Malaga for reasons I didn’t care to ascertain—and spend his spare time looking after his record collection, his apartment, and his car was far more poetic than wasting his time imitating León Felipe or at best (so to speak) Sanguinetti. I was totally noncommittal when Enrique asked my opinion (as if it might be an irreparable loss for lyric poetry in Spanish or Catalan, for God’s sake). I told him I was sure he had made the right decision. He didn’t believe me.

That night, or at one of the other four dinners, the conversation turned to children. It was inevitable: poetry and children. I remember (and this I remember with absolute clarity) Enrique confessing that he would like to have a child. The experience of childbirth, those were his words. Not to share it with a woman, no, he wanted it for himself: carrying the child for nine months inside him and then giving birth. I remember, as he said this, I felt a chill in my blood. The two women looked at him tenderly, but I had intimation, and this was what chilled me, of what would happen years later, and not many years, unfortunately. When the feeling faded—it was brief, just a twinge—-Enrique’s declaration struck me as a quip, unworthy of reply. Predictably, the others all wanted to have children, and I, predictably, didn’t, and in the end, of the four who were present at that dinner, I am the only one who has a child. Life is mysterious as well as vulgar.

It was during the last dinner, when my relationship with the Mexican woman was on the point of exploding, that Enrique told us about a magazine that he contributed to. Here we go, I thought. He corrected himself immediately: That we contribute to. The plural puzzled me momentarily, but then the penny dropped: Enrique and his girlfriend. For once (and for the last time) the Mexican woman and I were in agreement: we asked to see the magazine straight away. It turned out to be one of the numerous periodicals sold at newsstands, with stories on subjects ranging from UFOs to ghosts, and taking in apparitions of the Virgin, little-known pre-Columbian civilizations, and paranormal events in general. It was called Questions & Answers, and I think it’s still being published. I asked—we asked—how exactly they contributed. Enrique (his girlfriend said practically nothing during this last dinner) explained: on weekends they went to places where there had been sightings of flying saucers; they interviewed the people who had seen them, examined the surroundings, looked for caves (that night Enrique affirmed that many mountains in Catalonia and the rest of Spain were hollow); they stayed up all night, snug in their sleeping bags, with a camera at the ready, sometimes just the two of them, more often in a group of four, five, or six. It was a nice way to spend the night, out in the open, and when it was over, they wrote a report, part of which was published with photos in Questions & Answers (so what happened to the rest of it?).

That night, after dinner, I read a couple of the articles that Enrique and his girlfriend had contributed to the magazine. They were badly written, dull, pseudoscientific—the word science, in any case, was used several times—and insufferably arrogant. He wanted to know what I thought of them. I realized that my opinion no longer mattered to him in the least, so, for the first time, I was absolutely frank. I suggested changes; I told him he should learn how to write. I asked him if they had editors at the magazine.

Once we got out of the apartment, the Mexican woman and I burst into uncontrollable laughter. I think it was later that week that we split up. She went to Rome; I stayed on in Barcelona for another year.

For a long time I had no news of Enrique. In fact I think I forgot all about him. I went to live on the outskirts of a village near Girona with five cats and a dog (a bitch, actually). I rarely saw my old friends and acquaintances, although from time to time one of them would drop in and stay with me, never for more than a couple of days. Whoever the visitor happened to be, we would end up talking about friends from Barcelona or Mexico, but I can’t remember any of them mentioning Enrique Martin. I only went down to the village once a day, with the dog, to buy food and rummage through my post office box, where I would often find a letter from my sister in Mexico City, which seemed to have changed beyond recognition. The other letters, few and far between, were from South American poets adrift somewhere in South America, with whom I engaged in desultory exchanges, tetchy and melancholic by turns, just like me and my correspondents, coming to the end of youth, coming to accept the end of our dreams.

One day, however, I received a different sort of letter. Actually, it wasn’t, strictly speaking, a letter. On the backs of two cards—invitations to a kind of cocktail party thrown by a Barcelona publisher to launch my first novel, a party which I did not attend—someone had sketched a rather rudimentary map, next to which were written the following numbers:

3860 + 429777 -469993? + 51179 -588904 + 966 -39146 + 498207856

Unsurprisingly, this missive was not signed. The anonymous sender had evidently attended the launch. I made no attempt to decipher the numbers, although I guessed it was an eight-word sentence, no doubt dreamt up by one of my friends. There was nothing particularly mysterious about it, except, perhaps, for the sketches. They showed a winding path, a tree beside a house, a river dividing into two, a bridge, a mountain or a hill, a cave. On one side, a simple compass rose indicated north and south. Beside the path, in the opposite direction to the mountain (in the end I decided it must be a mountain) an arrow pointed the way to a village in Ampurdán.

That night, back at my house, while I was preparing dinner, it struck me that it must have been sent by Enrique Martin. I imagined him at the launch, talking with some of my friends (one of whom must have given him the number of my post office box), making scathing remarks about the book, working the room with a glass of wine in his hand, saying hello to everyone, loudly inquiring whether or not I would put in an appearance. I think I felt something like contempt. I think I remembered my exclusion from White Rope, which was ancient history by then.

A week later I received another anonymous letter. Again it was written on one of the invitations to my book launch (he must have picked up several), but this time I noticed some differences. Under my name he had written out a line by Miguel Hernandez, about happiness and work. And on the other side, the same numbers and a map, radically different from the first one. At first I thought it was just scribble: tangled, intersecting, broken, dotted lines, exclamation marks, drawings rubbed out and superimposed. Finally, after scrutinizing it for the umpteenth time and comparing it with the first cards, I cottoned on: the new map was a continuation of the first one; it was a map of the cave.

I remember thinking we were too old for this sort of joke. One afternoon I leafed through an issue of Questions & Answers at a newsstand. I didn’t see Enrique’s name among the contributors. After a few days I forgot all about him and his letters.

Some months went by, three, maybe four. One night I heard the sound of a car pulling up outside my house. I thought it must have been someone who had got lost. I went out with the dog to see who it was. The car had stopped next to some brambles, with the motor running and the lights on. For a while, nothing happened. From where I was standing I couldn’t see how many people were in the car, but I wasn’t scared; with that dog at my side I was hardly ever scared. She was growling, keen to hurl herself on the strangers. Then the lights went off, the motor stopped, and the car’s single occupant opened the door and greeted me like an old friend. It was Enrique Martin. I’m afraid I didn’t reciprocate. The first thing he asked me was if I had received his letters. I said yes. No one had interfered with the envelopes? The envelopes were still properly sealed? I replied in the affirmative and asked him what was going on. Problems, he said, looking back at the lights of the village and the curving road, beyond which there was a stone quarry. Let’s go inside, I said, but he didn’t budge. What’s that? he asked, meaning the lights and the noises from the quarry. I told him what it was and explained that at least once a year, I had no idea why, they kept working till after midnight. That’s strange, said Enrique. Again I said, Let’s go in, but either he didn’t hear me or he pretended not to. I don’t want to bother you, he said, after my dog had sniffed him. Come in, we’ll have a drink, I said. I don’t drink alcohol, said Enrique. I was at your book launch, he added. I thought you’d come. No, I didn’t go, I said. Now he’s going to start criticizing my book, I thought. I was hoping you could look after something for me, he said. That was when I realized he was holding a kind of package in his right hand; it looked like a bundle of A4 sheets. He’s gone back to writing poetry, I thought. He seemed to guess what I was thinking. It isn’t poetry, he said with a smile that was at once forlorn and brave, a smile I hadn’t seen for many years, not on his face, at any rate. What is it, I asked? Nothing, just some stuff. I don’t want you to read it; I only want you to look after it. All right, let’s go inside, I said. No, I don’t want to bother you, and anyway I’m late; I have to get going right away. How did you know where I live? I asked. Enrique named a mutual friend, the Chilean who had decided that one Chilean was enough for the first issue of White Rope. He’s got a nerve, giving out my address, I said. You’re not friends anymore? asked Enrique. I guess we are, I said, but we don’t see each other much. Anyway I’m glad he did; it’s been really nice tosee you, said Enrique. I should have said: And to see you, but I just stood there. Well, I’m off, said Enrique. Then there was a series of very loud noises, like explosions, coming from quarry, which made him jumpy. I reassured him. It’s nothing, I said, but in fact it was the first time I had heard explosions at that time of night. Well, I’m off, he said. Take care, I said. Can I give you a hug? he asked. Of course, I said. What about the dog, he won’t bite me? It’s a she, I said, and no, she won’t.

For the next two years, while I lived in that house outside the village, I complied with Enrique’s request and kept his packet of papers intact, fastened with tape and string, among old magazines and my own papers, which, it doesn’t go without saying, multiplied at an alarming rate during that period. The only news I had of Enrique was supplied by the Chilean from White Rope; one day we talked about the magazine and the old days, and he clarified his role in the elimination of my poems, which was nonexistent, so he said, and so I concluded after listening to his account, not that it mattered to me by then. He told me that Enrique had a bookshop in the Barrio de Gràcia, near his old apartment, which, years before, I had visited five times with the Mexican woman. He told me that Enrique and his wife had split up and no longer contributed to Questions & Answers, and that his ex was working with him in the bookshop. They weren’t living together anymore, he said, they were just friends, and Enrique gave her the job because she was out of work. And how’s his bookshop going? I asked. Really well, said the Chilean; apparently he got a good severance package from the company where he’d been working since he was a teenager. He lives on the premises, he said. Behind the bookshop, in two smallish rooms. The rooms, I later found out, opened onto an interior courtyard, where Enrique grew geraniums, ficus, forget-me-nots, and lilies. There were two doors in the shop front and a metal screen that he pulled down every night and locked, as well as a little door that opened onto the building’s entrance hall. I didn’t feel like asking the Chilean for the address. I didn’t ask him whether or not Enrique was writing either. But shortly afterward I received a long letter from the man himself, signed this time, informing me that he had been in Madrid (I think he was writing from Madrid, but I’m not sure anymore) for the famous International Science Fiction Writers’ Convention, No, he wasn’t writing science fiction (I think he used the expression SF); he had been sent as a special correspondent by Questions & Answers. The rest of the letter was muddled. He talked about some French writer whose name didn’t ring a bell, according to whom we are all aliens, “we” meaning every living creature on planet Earth; exiles, all of us, wrote Enrique, or outcasts. Then he explained just how it was that the French writer had reached this harebrained conclusion.

But that part was incomprehensible. He mentioned the Thought Police, speculated about Hyper-dimensional tunnels, and went gabbling on the way he used to in his poems. The letter ended with an enigmatic sentence: All who know are saved. Then there were the conventional closing formulae. It was the last letter he wrote to me.

Again it was our mutual Chilean friend who filled me in and told me the latest news. We were having a meal together, during one of my increasingly frequent trips to Barcelona, and in the course of the conversation he let it drop, casually, without dramatizing the facts.

Enrique had been dead for two weeks. It had happened more or less like this: one morning his ex-wife, now his employee at the bookshop, arrived and found the premises still locked. This surprised her, but she was not alarmed, because Enrique sometimes slept in. For such occasions she had her own key, with which she proceeded to unlock the metal screen and then the glass door in the shop front. She went straight to the apartment at the back, and there she found Enrique hanging from a rafter in his bedroom. The sight almost gave her a heart attack, but she pulled herself together, called the police, shut the shop and waited outside, sitting on the curb, crying, I suppose, until the first patrol car pulled up. When she went back in, she was surprised to find Enrique still hanging from the rafter. While the police were asking her questions, she noticed that the walls of the room were covered with numbers, big and small, some painted with a stencil, others with spray paint. She remembered the policemen taking photos of the numbers (659983 + 779511 -336922, that sort of thing: incomprehensible) and Enrique looking down at them dismissively. The ex-wife turned employee thought the numbers represented debts he had run up. Yes, Enrique was in debt, not much, not enough for anyone to want to kill him, but he did have debts. The policemen asked her if the numbers had been on the walls the previous day. She said no. Then she said she didn’t know. She didn’t think so. She hadn’t been in that room for a while.

They checked the doors. The one that opened onto the entrance hall was locked from the inside. They found no sign that any of the doors had been forced. There were only two sets of keys: she had one and they found the other next to the cash register. When the investigating magistrate arrived, they took Enrique’s body down and removed it from the premises. The findings of the autopsy were conclusive: he had died almost instantly, by his own hand, another one of Barcelona’s frequent suicides.

Night after night, in the solitude of my house outside Girona, which I would soon be leaving, I thought about Enrique’s suicide. I found it hard to believe that the man who had wanted to have a child, who had wanted to give birth to it himself, could have been so thoughtless as to let his employee and ex-wife find his body hanging—naked? Clothed? In pajamas?—and possibly still swinging from a rafter in the middle of the room. The business with the numbers was more believable. I had no trouble imagining Enrique busy at his cryptography all night long, from eight when he shut the bookshop until four in the morning, a good time to die. Naturally I elaborated various hypotheses in an attempt to explain the manner of his death. The first was directly related to the last letter I had received from him: suicide as a ticket home to the planet of his birth. According to the second hypothesis, he had been murdered in one of two ways. But both strained credibility. I remembered our last meeting, in front of my house, how nervous he had been, as if he were being followed, or hunted.

On my subsequent visits to Barcelona, I compared notes with Enrique’s other friends. No one had noticed any significant change in him; he hadn’t given sketched maps or sealed packets to anyone else. Concerning one aspect of his life, however, the information was contradictory or incomplete: his work for Questions & Answers. Some said that his association with the magazine had come to an end long ago. According to others, he had been a regular contributor right up to his death.

One afternoon when I had nothing to do, after sorting out a few things in Barcelona, I went to the office of Questions & Answers. The editor received me. Had I been expecting a shady character, I would have been disappointed. He could have been an insurance salesman, pretty much like any magazine editor. I told him Enrique Martin was dead. He didn’t know, said he was sorry to hear it, and waited. I asked if Enrique had been a regular contributor to the magazine and, as I expected, he replied in the negative. I mentioned the International Science Fiction Writers’ Conference, which had been held recently in Madrid. He told me that his magazine had not sent anyone to cover the event. Fiction, he explained, was not their domain; they were investigative journalists. Although personally, he added, he was a science fiction fan. So Enrique went on his own account, I thought aloud. He must have, said the editor, in any case he wasn’t working for us.

Before everyone forgot about Enrique, before his friends grew accustomed to his definitive absence, I got his ex-wife and ex-employee’s phone number and called her. She didn’t remember me at first.

“It’s me,” I said, “Arturo Belano. I went to your apartment five times; I was living with a Mexican woman.”

“Ah yes,” she said.

Then there was a silence and I thought there was a problem with the line. But she was still there.

“I called to say how sorry I was to hear what happened.”

“Enrique went to your book launch.”

“I know, I know.”

“He wanted to see you.”

“We did see each other.”

“I don’t know why he wanted to see you.”

“I’d like to know too.”

“Well it’s too late now, isn’t it?” 1 guess so.

We talked for a while more, about her nerves, I think, and the state she was in, then I ran out of coins (I was calling from Girona) and we got cut off.

A few months later I left the house. I took the dog with me. I gave the cats to some neighbors. The night before leaving I opened the package that Enrique had given me to look after. I thought I’d find numbers and maps, maybe some sign that would explain his death. There were fifty A4 sheets, neatly bound. There were no maps or coded messages on any of them, just poems, mainly in the style of Miguel Hernandez, but there were also some imitations of León Felipe, Blas de Otero, and Gabriel Celaya. That night I couldn’t get to sleep. My turn to flee had come. |