|

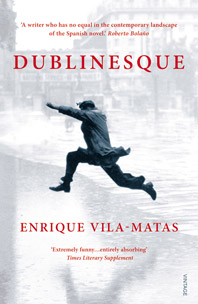

DUBLINESQUE

ALBERTO MANGUEL *

There is a kind of literary fiction that feeds on itself, like an introverted cannibal. Instead of accepting Coleridge's dictum that a reader must voluntarily suspend disbelief, the novels of this genre proclaim that literature is an artifice, ask the reader for an opinion of the story, put on the airs of a critical or historical essay, and bring on to the page real people who are made to perform the roles normally left to fictional characters. The French excel at this, perhaps because Denis Diderot is the grandfather of the genre, but worthy followers include such masters as Jorge Luis Borges, WG Sebald and the Spanish writer Enrique Vila-Matas. In this self-reflective area of fiction, Vila-Matas has a province of his own. I have some 15 books of his on my shelves, and each one chomps off another piece of the fictional beast: Bartleby & Co concerns itself with writers who prefer not to write; Explorers of the Abyss with titles that don't require books; Montano with readers who require nothing but their books and are possessed by what they read. We are now down to the last shreds of literature and can wonder, once the last bone has been gnawed, what Vila-Matas will write about.

Fortunately, the days of famine are not yet here, and from his latest raid into the literary jungle Vila-Matas has brought home a fine specimen of that most endangered of intellectual species, the literary publisher. In Dublinesque, superbly translated by Rosalind Harvel and Anne McLean, Samuel Riba, a 60-year-old Catalan alcoholic publisher and bibliophile, heeding the apocalyptic voices that trumpet the imminent end of the book in our digital dark age, decides to travel to Dublin with a group of friends and hold there, on Bloomsday, a funeral for the book. Riba has never been to Dublin, but he once dreamt that he was sitting outside a Dublin pub, crying because he had started to drink again. On the strength of that dream, which for him is an omen, he sets off with his companions to the city of Joyce.

The list of "real people", most of them writers, who pop up in the account of Riba's ritual voyage is impressive: Julien Gracq, Claudio Magris, Georges Perec, Hugo Claus, Borges, Carlo Emilio Gadda, and many other luminaries of modern literature. Some may or may not exist (such as the aphoristic Czech author Vilém Vok), some may appear as a gift-bearing spirit (Philip Larkin, for example, gives the novel its title). Some occupy more space than they might perhaps deserve – the presence of Paul Auster among fiction's innovators is a little puzzling – but all together conjure up a sort of literary smorgasbord surrounding the great absence, the author of Ulysses.

Vila-Matas is not above chewing up bits of the master, from the Dublin landmarks Joyce celebrated, to the various fictional techniques in Ulysses, to choice morsels of the work itself. Thus the mysterious man in the mackintosh who haunts Paddy Dignam's funeral in the Hades section of Ulysses appears in Dublinesque as a ghostly incarnation of the many things that Riba has longed for in his successful publishing career, now coming to an end in the twilight of his gods: to have met one of the great ones such as Samuel Beckett, to have discovered a new literary genius, to have trusted literature more than the bottle, to have had faith in that literary truth which someone like Vila-Matas is attempting to demolish.

And yet, the study of ruins is a worthy artistic endeavour. Beckett noted that while Joyce proceeded by constantly adding to the edifice, he himself worked by constantly subtracting, stone by stone. Based on this assertion, Vila-Matas grants Riba something like an epiphany. He realises that : “The story of the Gutenberg age and of literature in general had started to seem like a living organism that, having reached the peak of its vitality with Joyce, was now, with his direct and essential heir, Beckett, experiencing the irruption of a more extreme sense of the game than ever, but also the beginning of a steep decline in physical form, ageing, the descent to the opposite pier to that of Joyce's splendour, a freefall towards the port of the murky waters of poverty where in recent times, and for many years now, an old whore walks in an absurd worn-out raincoat at the end of a jetty buffeted by the wind and the rain.

*Review in The Guardian (16-06-2012) |