| ENRIQUE VILA-MATAS | LA VIDA DE LOS OTROS | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

Tibet 2004 ALBERTO MANGUEL

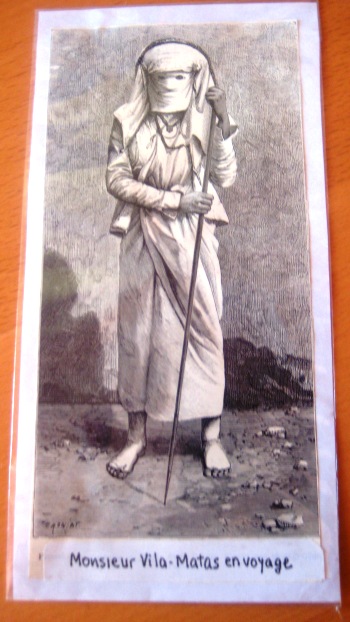

“Monsieur Vila-Matas en voyage” Envío de Alberto Manguel a V-M en diciembre 2007 |

MONTANO, THE SURVIVAL OF LITERATURE ALBERTO MANGUEL Shelley (and later Paul Valéry) suggested that all literature might be the work of a single Author and that, throughout the ages, writers have merely acted as His (or Her) amanuenses. A visit to any large bookshop today seems to confirm this thesis: an infinitude of almost identical accounts of Da Vinci conspiracy theories, immigrant life in London or Los Angeles, dysfunctional families in Brooklyn or Glasgow, offer readers the impression of bewildering déjà vu. If literature has one Author, it’s time for Her (or Him) to change subjects. The figure in the carpet is wearing thin. Enter Enrique Vila-Matas. For the past 30 years, aware of the futility of telling interesting stories in a world bent on stolid repetition, Vila-Matas has chosen to construct his books out of bits and pieces of the available literature itself, renewing even the idea of collage or bricolage so dear to the practitioners of experimental art in the early 20th century. Vila-Matas, however, never gives the impression of experimenting; there’s no feeling of trial-and-error in his work. Rather, what he does is hold with the reader an intelligent conversation (monologue is perhaps a better word) made up of quotations, literary anecdotes, personal readings and startling associations, that build up an illuminating and brilliant farrago. If he has any ancestors, they belong to the 17th and 18th centuries: Sir Thomas Browne and Robert Burton, Denis Diderot and Lawrence Sterne. All of Vila-Matas’s books have something of Tristram Shandy. After several excellent books, admired almost secretly by a restricted group of readers, Vila-Matas achieved international fame in 2000 with Bartleby & Co., an exploration of the limits of literature through a catalogue of writers (real and imaginary) who, like Melville’s famous scrivener, ‘prefer not’ to write. Absence of literature is the subject of this book (just as absence of action is the subject of Sterne) and around that absence, Vila-Matas wove a splendid meditation on the morose nature of our time that, under the pretence of febrile activity and snappy urgency, sits and does nothing. If a scarcity of work was the subject of Vila-Matas’s Bartleby, then a surfeit of works is that of Montano, published in Spanish two years later and only now available in English in a superb translation by Jonathan Dunne (whose name is shamefully absent from the cover.) Montano, the narrator’s son, is a writer (literally) sick of literature, and yet obsessed with what he sees as its precariousness. He has written a ‘dangerous’ book on writers who have given up writing (Bartleby & Co. comes of course to mind) and now, secluded in his house in Nantes, is himself the victim of writer’s block. Montano is disillusioned with the world today: everything in it, he believes, conspires against the literary act, and our intellectual, moral, ethical task is to fight against its enemies. Haunted by ‘Montano’s sickness’ (that is the book’s title in Spanish,) the narrator gradually begins to allow the world of literature to possess him body and soul: by means of a wealth of literary references, he will become Literature incarnate, he will give his mind and memory over to the writings of others, he will be, in the flesh, the infinite, all-encompassing universal Library. Precisely because literature enables us to understand life [the narrator writes] it tells us what can be, but also what could have been. There is nothing sometimes further away from reality than literature, which is constantly reminding us that life is like this and the world has been organised like that, but it could be otherwise. There is nothing more subversive than literature, which is concerned to return us to true life by exposing what real life and History smother. Montano is not an apocalyptic novel, it is not an elegy, it has none of the facile gloom of those who warn of the end of books and lend a helping hand in the closing of the libraries. Montano is an intelligent and joyful paean that proclaims not the demise, but the survival of literature. In the last paragraph, the narrator bids Montano farewell and then meets Robert Musil, the author of the never-completed masterpiece The Man Without Qualities, standing next to an abyss. Though Musil’s cities were mainly Berlin and Vienna, it was Prague that was for him emblematic of literary life, and it was the Prague periodicals Prager Presse and Bohemia that published many of his writings. Prague stood for literature itself. ‘It is the air of the time, the spirit is threatened,’ the narrator says to him. The long-dead author looks towards the horizon and declares: Prague is untouchable, it’s a magic circle, Prague has always been too much for them. And it always will be. |

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| www.enriquevilamatas.com | |||||||||||