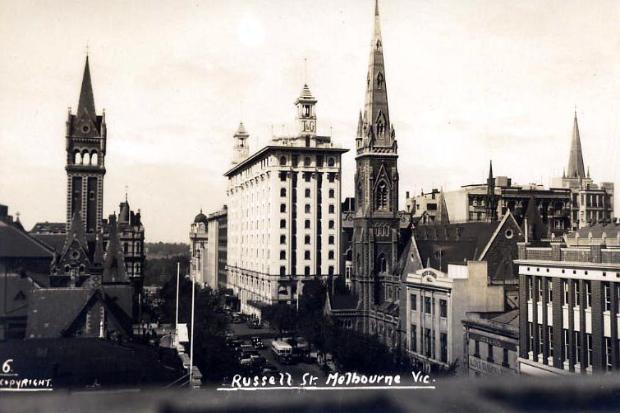

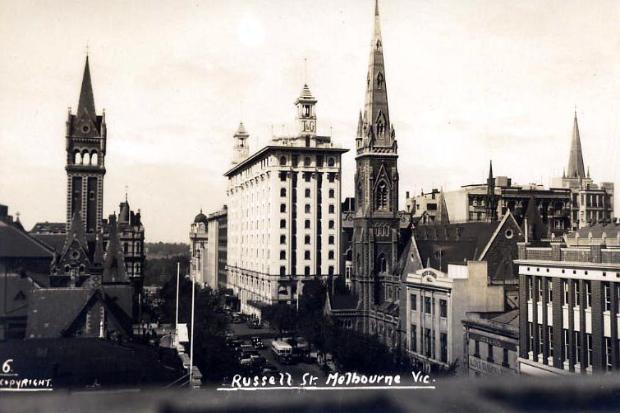

Melbourne 1940

Melbourne 1950

Melbourne 1960

JWW en Meanjin

Melbourne 2014

|

ENTREVISTA PARA AUSTRALIA

JOHN WILLIAM WILKINSON

JOHN WILLIAM WILKINSON: You’ve been the interviewee hundreds of times, but on certain occasions you’ve also been the interviewer, haven’t you?

ENRIQUE VILA-MATAS: In August 1967, when I was seventeen and studying journalism, I suddenly found myself—owing to a conjunction of unforeseeable events—writing for a movie magazine called Fotogramas, which in those days was the only modern magazine in Spain. It was my first job. Naturally I was delighted, but soon found myself in serious trouble because I’d assured them I knew English and so they went and handed me Julie Gilmore’s extraordinary Marlon Brando interview. They’d paid a lot of money for it and were convinced it was going to be a real highlight of the issue. Not wishing to admit there was no way I was going to be able translate it, I invented the whole thing from start to finish and made Brando say a whole lot of nonsense. Nobody cottoned on to the fraud, though one Barcelona newspaper did say that Brando seemed to have gone mad. It all worked out so well, from then on I followed the same procedure with the other celebrities I was sent to interview when they passed through Barcelona. I just made them all up. Nureyev, Patricia Highsmith, Anthony Burgess, Fritz Lang … Without realising it, I learnt to create fiction thanks to those bogus interviews.

JWW: Why should I believe what you’re telling me now, given that your novels are bulging with false quotations and red herrings?

EV-M: You are quite right to be wary, but you’d be far better off believing me. Why don’t you try, even if only to politely return the courtesy I’ve bestowed on you by considering your question to have been asked in all seriousness in the first place?

JWW: It would thus follow that truth—which apparently goes hand in hand with seriousness—boils down to a question of courtesy. Be that as it may, I do find a great deal of humour in your novels, precisely in their most sullen passages.

EV-M: I’m not at all sure that truth is a question of courtesy. Though I am sure that courtesy and humour go hand in hand. The novelist from Trieste, Italo Svevo, just minutes before he died, asked his son-in-law to give him a cigarette, which he refused to do. ‘It’d be the last one,’ Svevo murmured. He didn’t say it to arouse pathos, but, rather, to prolong an old joke: it was an invitation to laugh, an attempt at comical relief as he bid farewell to the world. When the other Triestine writer Humberto Saba had the scene described to him, he remarked that humour is the highest form of courtesy.

JWW: I suspect you’ve just made up that Saba quote. But, anyway, your novels, despite having little in common with the typical bestseller, are up there among the top ten virtually from the moment they hit the shops, often remaining there for weeks on end. What’s your secret?

EV-M: One fine day, years ago, I observed the following:

- That there were interesting writers: structural and technical innovators, rather complicated, prone to difficulty, with a tremendous load of intertextuality that made what they write seem intelligent; and

- There were lousy fiction writers, cynical and commercial, lumping everything together in a mechanical way to manipulate the reader but at the same time grotesquely simplify everything in an enthusiastic, childlike way …

It also seemed to me that authors of both tendencies think their readers are stupid. So it occurred to me that the ideal thing would be to write a novel with the richness and challenge of literary innovation and also with a level of emotional and intellectual difficulty (something that pushed the reader to face problems instead of ignoring them). However, this had to be done in such a way that it was also a pleasure to read. In other words, the reader would feel as if I were communicating with him/her on every page, trying to connect in the most authentic way possible.

JWW: I’d say you’ve achieved that, or at least in part, in view of the many faithful readers you have, not only in Spain and Latin America, but also in France, Italy and Portugal, countries where, if not enshrined among the fully established, you are considered a cult author. Don’t you find it strange that you haven’t been more successful in English-speaking countries? Could this be put down to poor translations? Or is there perhaps another explanation?

EV-M: In England and the United States only about 5 per cent of books published are translations. This very much limits the area of action for European writers, especially if they happen to be Spanish. Even so, things have been looking up in the last couple of years, at least in my particular case.

I made up my mind to perform the ‘English leap’ and, well, you might say I’m getting there. Not long ago, Joanna Kavenna dedicated two pages of the New Yorker to my work and wrote: ‘a Catalan writer who has established himself over four decades as arguably Spain’s most significant contemporary literary figure’. And Jacqueline McCarrick in the Times Literary Supplement said of one of my latest novels: ‘In Dublinesque Vila-Matas has created a masterpiece.’ Anne McLean’s excellent recent translations have certainly been a great help.

In October 2014, New Directions will publish two books, also translated by Anne McLean: Brief History of Literature and Kassel Does not Invoke Logic (the title of the English language version will be Cassell). It’s been an extremely slow process, but I prefer to regard myself as an unhurried traveller. There is a reason one of my books is titled The Slowest Traveller.

JWW: Before asking you about your experience during the Kassel festival, would you please shed some light on something I find intriguing. Prior to Dublinesque (2010 in Spanish; 2012 in English), your characters’ lives unfold in your native Barcelona, or you place them in Lisbon or the Azores, Naples or Veracruz, and they more often than not show up in Paris. This is the case in Never Any End to Paris, which, now that I come to think of it, was a veritable farewell to the city that so enchanted you in your youth. I imagine it was because you had already decided on that ‘English leap’. Yet instead of starting off in London or New York, you ventured into Dublin’s linguistic and literary bog lands. Could you tell me why?

EV-M: I wanted to write a novel but didn’t know what about. It was May 2008 and all I had was a short story with an ‘English atmosphere’ called ‘East End’,1 a story that came from my admiration of the sense of alienation in David Cronenberg’s film Spider.

That’s all I had when I was suddenly invited to join the Order of Finnegans. They told me that if I wished to be named a Knight of the Order on the roof of the Martello tower I’d have to travel to Dublin on 16 June. So I went. On that very day early in the morning all the knights gathered there glimpsed a ghost in the fog, right beside the cemetery gates. Could that have been Macintosh, who appears eleven times in Ulysses and of whom nothing is known? Dublinesque, in which Riba, the hero, is like Spider’s double, emerged from that apparition.

JWW: Before you start telling me about Kassel, since you mention David Cronenberg, and taking into account your record of being an extravagant falsifier of interviews for Fotogramas, wouldn’t it be right to say that cinema has influenced you almost as much as literature?

EV-M: Although I do now recognise the superiority of the masters of classic cinema, my literary education came from watching avant-garde cinema from the sixties. It all seemed so amazingly natural, to the point that since then the cinema has never ceased to be associated with that era of endless stylistic innovations. I grew up in the age of Godard. That should be scrawled across the dust jackets of all my books as a warning to every buyer. Godard wanted to make fiction films that were like documentaries and documentaries that were more like fiction, while I’ve written—or at least tried to—autobiographical narratives like essays and essays like narratives.

JWW: There’s not one of your novels that I can imagine ever being made into a film—has any filmmaker ever toyed with the idea?—and I say this as a tribute to the purity of literary distillation evident in each and every one of them. I’d say it’s owing to the sheer wealth of verbal complexity, which ends up clarifying more than it clouds, and which is why I devour them in one sitting. Anyway, unlike so many others jostling on the shelves, your novels don’t seem to be written with a future film script in mind. Besides, as you’ve just pointed out, your fiction leans more towards an essay than documentary style.

EV-M: My books are so ‘literary’ that it seems they don’t allow a gap in which a conventional screenplay could fit. I believe this fact is linked to the often-encountered difficulty in summarising my books. Whenever I get something new published and I am asked what the book is about, I tend to say that it’s about ‘everything, absolutely everything written in the book, not a word less, not a word more’. If I were a filmmaker I would make one of my ‘unfit’ books into a movie and to do that I would choose the one that seems to be the least filmlike: Brief History of Literature. Among other things, that book talks about the Shandy conspiracy of the twenties. It would be a success. Though, of course only if the filmmaker working on this ‘almost impossible adaptation’ were talented.

JWW: During your formative years in Franco’s isolated, suppressed, grotesque Spain, France was highly attractive to young people fed up with the regime. You mentioned Godard, but besides filmmakers, France, or should I say Paris, offered an endless rollcall of poets, novelists, philosophers, artists, chefs and singers … and you, like so many others, fell under their spell. Yet almost nothing remains of that cultural hegemony. Why is that so, do you think?

EV-M: When I moved to Paris, in 1974, there was already much talk claiming that the show was over. Tel Quel, with its unreadable texts, was all the rage, and only Roland Barthes came across as being even remotely sensible. But Paris is always like that, has been for centuries. It’s where you experience at first hand the disasters that end up affecting the whole world. Culturally, we’re going from bad to worse, and there’s nowhere like Paris to perceive that. Flaubert expressed it with great lucidity: ‘A time will come in which all men will be “businessmen” (by which time, thank God, I will be dead). Our nephews will be worse off than we are. Future generations will be tremendously vulgar.’

JWW: Flaubert was right about so many things … and now that most Western countries have their President Bouvard and their Prime Minister Pécuchet, where are we to look? Have you any idea about what’s going on in Australia?

EV-M: Australia arouses my curiosity, being as it is the antipodes of Barcelona. But I doubt very much that it’s the antipodes of our spirit, of our way of life. Moreover, I’m sure we have much in common; for example, the same unbearable ordeal inflicted on us by politicians, corruption and incompetence.

JWW: Don’t even mention it. Let’s focus our attention today on literature. Almost nothing is known of Australian writers in Spain, except, perhaps, Peter Carey. Not even Patrick White has ever had more than a handful of readers, though maybe that can be attributed to bad translations. Do you think your novels are worthy of readers in Australia, a country that, unlike Spain, is so unaccustomed to translations?

EV-M: More than once it’s been said of me that I’m ‘the most Argentine of Spanish writers’. But, then again, they also say I’m the most Portuguese, and a few months ago, in the Nouvel Observateur I was called ‘the closest thing to a French person among the Barcelonan writers’. The New Yorker has even labelled me as the most New Yorker of Catalan writers. What is the reason for this phenomenon? Is it because I’m from nowhere in particular? Or maybe it’s because I’m from wherever I happen to be at the time. I imagine my work being read anywhere at all in Australia and an Australian reader looking up from the page and saying: ‘This writer’s the most Australian of Spanish writers.’

JWW: I seem to remember it was Rodolfo Fogwill who, on being asked where he was from, answered: ‘Buenos Aires, like everyone else.’ So now we’ve established that you, like Fogwill, or the Pope, or even myself, are from Buenos Aires, a city that, Duchamp claimed, doesn’t exist, would you tell me where you stand with modern technology? I would appreciate you giving me an answer without imitating an Argentine accent.

EV-M: Until December 2000 I absolutely refused to have anything to do with computers. I even went so far as to make my aversion publicly known in a documentary for a television station in Barcelona. But only one month later, in January 2001, I suddenly became a computer freak, a nerd, which is what I still am: an out-and-out hikikomori, like in my novel Dublinesque.

To clarify: the hikikomori are autistic IT fans, Japanese youngsters who in order to avoid external pressures react with a complete social withdrawal. In fact, the Japanese word hikikomori means ‘pulling inward’. They lock themselves in a room inside the home of their parents for long periods of time, generally years. They feel sad and barely have any friends; the majority of them sleep or lie around during the day and watch TV or spend their time on the computer throughout the night. Maybe the future belongs to the hikikomori.

JWW: Let’s hope not. Tell me about Kassel.

EV-M: Not a day goes by without me coming across yet another hikikomori. For instance in Kassel. I went there in September 2012, invited by Documenta to participate as ‘a guest writer in a Chinese restaurant’. A strange invitation, you might say. I was asked to spend my days writing in front of all comers in a Chinese restaurant near a park in Karlsaue. Not a soul came to see me, which meant I ended up spending the whole time eavesdropping on the Chinese and Germans. I don’t understand a word of either language, so I just imagined what they were saying. And, believe me, there were times I felt afraid. But the best part of the invitation was that I got to travel right to the very heart of avant-garde contemporary art and that’s precisely where I conceived the book (Kassel Does not Invite Logic) that I’ve been working on lately and that I’m really excited about: a kind of fictional press report about what I saw and what happened to me, or at least what I thought happened to me.

JWW: Well, having got this far, it’s now up to readers to decide whether I made up your answers or you who invented the questions. In any case, it is to be hoped that this interview is read by the hikikomori Vila-Matas, even if only out of courtesy.

EV-M: ‘Remember to be wary’ is what Vila-Matas occasionally remembers Stendhal wrote. And, well, what can I say? I’ve known him for some time now and know he’ll be somewhat perplexed when he reads this. But you can be sure he will only be simulating. One day I went to see him; I found him sitting before an electric typewriter and just like Jack Torrance in The Shining he’d been there for quite a while writing over and over the same sentence: ‘By popular request, he wrote again what he’s already written.’ |